Energy hungry data centres sprout around the world to satisfy AI’s demand for power: will it be enough?

By Ernest Granson

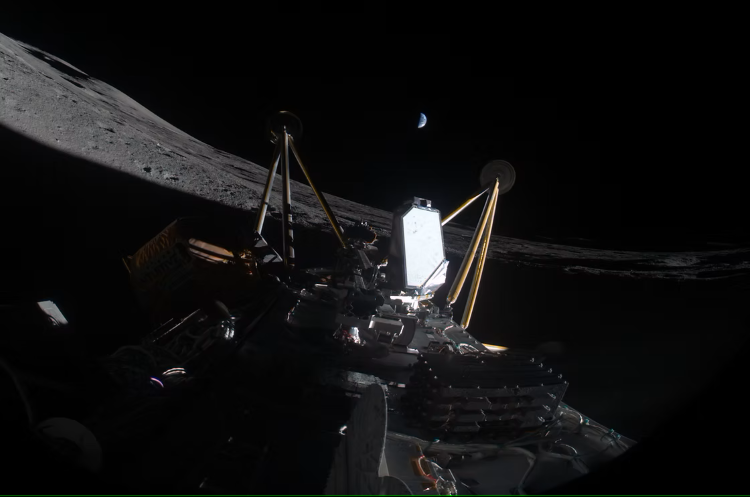

Demand for data centres has sky rocketed, and this writer means that in the literal sense of the word. In March of 2025, the first data centre to be placed on the moon. blasted off on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket housed inside Intuitive Machines LLC’s Athena lunar lander.

A data centre on the moon, you must be asking? It’s true, but not to mislead anyone, this data centre consists of a compact hardware module composed of an eight-terabyte solid state drive powered by a PolarFire SoC FPGA (system-on-chip field-programmable gate arrays) microchip.

Lonestar Data Holdings of St. Petersburg, Florida and Flexential Corp. of Charlotte, North Carolina, collaborated to develop this piece of equipment, and while this data centre is a miniature in comparison to the massive facilities on earth, it is a bonafide data storage unit that successfully executed file uploads and downloads, data encryption and decryption authentication as well as in-space data manipulation. This, despite the fact the Athena lander tipped over soon after landing on the moon, losing power and shutting down.

Why a data centre on the moon? According to Lonestar – “Lonestar is committed to pioneering lunar-based edge computing and storage solutions, ensuring that critical digital assets can be preserved independent of Earth-based infrastructure.” The company has set an ambitious program to follow up on the Athena mission planning to launch multi-petabyte data centres into lunar orbit and on the moon itself between 2027 and 2030.

Back here on earth, it’s also full speed ahead for the construction of data centres all around the world. According to digital publishers Visual Capitalist and Statista, as of March 2024, (the latest numbers available), there were 5,697 public data centres globally, i.e., commercially accessible. That number changes significantly to 11,800 if private data centres are included. Of those centres, 511 are considered hyperscale.

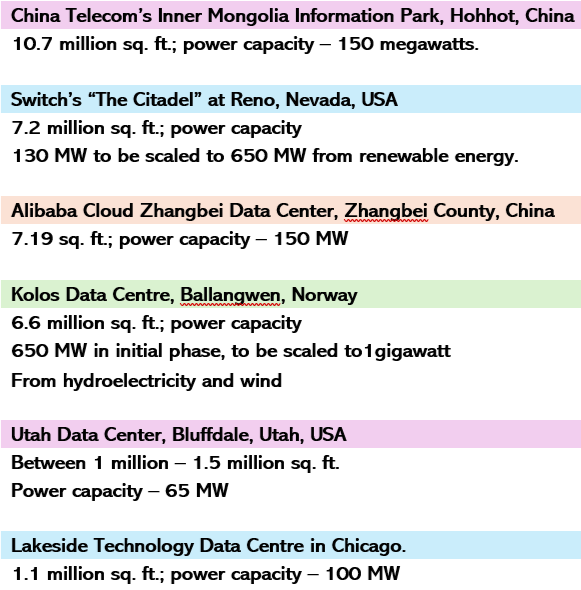

As you would suspect, hyperscale facilities refer to data centres substantially larger than what would be considered “average” centres. Various sources define hyperscale as those centres that are larger than 10,000 square feet, large enough to fit at least 5,000 servers and miles of cable.

For comparison’s sake, let’s take a look at some of the world’s biggest data centres as of this writing. Please note that the term “power capacity” is defined as the maximum amount of electrical power a data centre can draw from its utility sources or backup systems at any given time compared to “power consumption” which is the actual amount of electrical power used by the data centre at a given moment or over a period of time.

There are many more data centre projects in the proposal and planning stages, some of which could surpass those in this list including the much touted $500 billion joint Stargate AI Project announced in January 2025 by US President Donald Trump, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, Oracle Chairman Larry Ellison, and SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son. This joint venture will eventually result in the construction of 20 data centres across the U.S. The first two phases in Abilene, Texas now be being built will consist of facilities totalling 4 million sq. ft. with power capacity of about 1.2 GW.

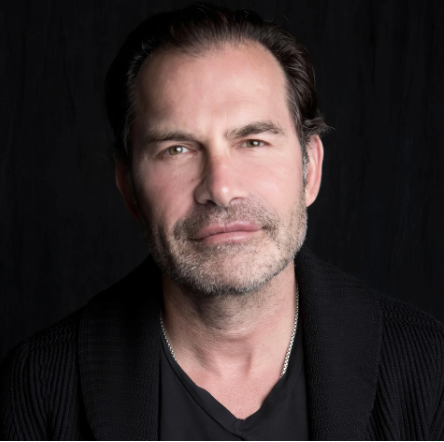

This brings us to Northern Alberta and another proposed hyperscale project named “Wonder Valley,” described by its chief backer and proponent, venture capitalist, Kevin O’Leary as the “largest AI Compute Data Centre Park on Earth.” The plan is for this 8,000 - acre facility to eventually operate with a power capacity of 7.5 GW, with the initial phase of 1.5 GW to be completed sometime in 2028. As pointed out in the list above, that’s drastically more power than even the Abilene Stargate facility.

At a keynote address which O’Leary delivered at the Data Center World 2025 Conference in Washington D.C. in April, O’Leary called the demand for data centres by AI businesses as a modern-day gold rush. And while that kind of a demand is desirable as a business case, he also stressed that transforming that need into a revenue producing business entity is a complex and difficult exercise, especially meeting the regulatory and permitting challenges as well as lining up the immense power supplies. Financing is dependent upon all of those factors, of course.

Wonder Valley – meet the Municipal District of Greenview

For O’Leary Ventures, a project of this enormity has become viable because of a unique piece of land located in Northern Alberta a short distance from Grande Prairie, a city with the population of about 70,000 and a trading area of nearly 300,000. That parcel of land is called the Greenview Industrial Gateway (GIG), created through a collaboration the Municipal District of Greenview, the County of Grande Prairie and the City of Grande Prairie, specifically to develop a world-class, heavy eco-industrial district, according to the GIG Area Structure Plan (ASP). The resulting administrative and physical structure of the GIG has opened the door for a project like Wonder Valley by providing the necessary utilities and streamlining the approval process. As O’Leary Ventures CEO and Wonder Valley project manager Paul Palandjian points out, North America and Canada in particular, offers the combination of being among the most stable, safest and secure place to store data, along with possessing an enormous amount of natural resources.

“Our thesis is that the two places in all of North America where there is a virtually endless supply of stranded natural gas and which are best suited to undertake a project of the size and scope that the hyperscalers are now looking for at a relatively low cost of power and with relatively low carbon intensity. Those two are Northwest Alberta and the MD of Greenview in particular and the Marcellus Shale formation in West Virginia,” says Palandjian. “Rather than having to build a massive infrastructure and pipeline to harvest and distribute that gas, we were intrigued by the idea that we could go to the source without the need for high transportation costs which means higher carbon intensity and ultimately a higher cost of power. Then take that natural gas, convert it to electrons by generating power behind the meter, convert those electrons to zeros and ones, and then send those zeros and ones out of the country, across the globe on fiber optic cable networks that already exist. That’s a very sound business concept. When we became aware of the Greenview Industrial Gateway, we were quickly convinced of its attractiveness of constructability. Dating back to 2012, the Municipal District of Greenview had the foresight to create an area structure plan, put into place a permitting and zoning plan and a mechanism by which they could quickly assemble large amounts of land owned by the Crown. They put a lot of dollars into surrounding highways and the fiber optic network. All of the things that you need to execute on a project of this size and magnitude are there. It's a true unicorn, I would argue, not just for North America, but globally. There's not a better piece of land that exists to do what we're contemplating doing.”

As of this writing, Palandjian says O’Leary Ventures has a purchase and sales agreement to acquire 7,850 acres and optioned another 5,000 acres. “The potential exists to increase the size and scope of the project from what is currently contemplated as 7.5 GW of power generation with 5.5 GW of IT load that would be rolled out over five phases and roughly 36 million sq. ft. of data centers in the 55 buildings,” he says. “We have already undertaken to create our own two prototype AI data centres that meet the modern requirement of the hyperscalers. One is a single storey high-density AI factory and the other is a two-storey building that is engineered for a combination of AI inference and cloud computing. The data centre campus of the future is likely to contain a combination of both. Essentially, the facility concept can be lifted to put anywhere to meet the highly specific needs of the hyperscalers in today's environment.”

With the purchase and sale agreement in place, O’Leary Ventures has begun assembling its development team including Beairsto & Associates Engineering Ltd., the Calgary civil engineering firm involved with the MD Greenview Master Plan, architectural design firm Gensler, headquartered in San Francisco, Sudlows Consulting, a subsidiary of Kent Engineering headquartered in Dubai but with a robust presence in Calgary, construction manager PCL Construction, real estate market research consultant Cushman & Wakefield, security engineering firm CenCore Group, engineering consultant, InPwr Inc., CSV Midstream Solutions, and the large projects division of Calgary-based KPMG.

“What we're putting together is dream team of highly seasoned, sophisticated world-class professionals to meet the highly specialized requirements that the off takers of a data center of this kind will require,” Palandjian says.

While all of those ingredients – land, transportation, water, years of permitting already under way by the MD of Greenview – are all supporting an accelerated project timeline for O’Leary Ventures at the GIG, there is one element that has to fall into place for this enormous project to be feasible and that is – power. As Palandjian puts it: “If you’re in the data centre business, you’re in the power business. You have to be because there’s just not enough power on the grid. Our conclusion is, to meet the growing need of hyperscalers we have to become the power company. That’s not to say we won’t partner with other firms who specialize in building, operating and maintaining power centres, but yes, we will be the utility – the water utility, the power utility and the data centre developer and operator.”

And in the short and medium term, the source of that power will be natural gas-fired turbines built on-site sourced from Greenview MD’s major reserve of natural gas. No power will be drawn from the grid. Nuclear and geothermal have been suggested within the industry as potential options for fuel sources but Palandjian says both sources are longer term solutions but aren’t cost effective yet. As an example, to build one GW of nuclear power is roughly $16 billion – to build one GW of natural gas generated power is roughly $1.5 billion. Therefore, the cost of power to get a return on that spend is much higher, and that cost gets passed through to the ultimate off taker.

Generating geothermal power, as well, is not considered cost-effective as of yet, although Palandjian suggests it’s possible to power a portion of a data centre to create a story of renewables, but in the case of Wonder Valley, to build the lowest carbon intensive data centre anywhere, the goal is to be carbon capture ready. “We're going to design and engineer our power solution to be able to sequester carbon, and we're sitting in the MD of Greenview, approximately 25 to 40 kilometers from the largest aquifer in all of Canada, that can handle the sequester registration of all of its carbon for the next two centuries. It's a geological attribute that no one else has,” he says.

Who’s buying? It’s the chicken and egg dilemma

To commit to this huge, enormous, gigantic – you pick the adjective – investment must mean O’Leary Ventures is confident of securing clients on the hyperscale list, right? Well, that’s the interesting question, says Palandjian. “This is the singular chicken and egg dilemma which exists for this industry,” he says. “Let me take a step back and say, if you were to build a modern-day office tower of a million square feet, there might be 1,000 potential credit worthy tenants that could occupy the floors of that building. You go whale hunting to bring in the best tenants to fill that building. In the data centre space, there are really only 15 or so potential tenants in the world. It’s like you're alien hunting in space for the hyperscalers by comparison. It's Google, it's Meta, it's Tesla or X.AI, Oracle, Alibaba, Amazon and the like. Each of them has an in-house capability to design and develop their own power and data centres. And because it’s not their core business, they're also looking to data centre developers like ourselves. And the questions they ask are, do you have the land? Do you have the power? How quickly can we get to market and start lighting up data centres there? Hyperscalers want to know that the power is there and that you can give them a power contract and know what their cost of power will be.”

“On the other hand, to finance that power build, the banks are going to say, ‘Well, do you have a tenant as an off taker for that power?’ So, you're not going to finance the power unless you have a tenant. You're not going to get a tenant unless the power is on the way. The world is waking up to this dilemma and we believe there is a solution to the problem and that’s because, more and more, we’re seeing U.S. chip suppliers become involved. Take for example, the recent move by NVIDIA to invest in AI hyperscaler CoreWeave. With NVIDIA committing $2 billion in debt to CoreWeave, as a hyperscaler you immediately have more confidence the project will be built. That is why we are actively in early discussions ourselves with both chip manufacturers and hyperscalers to resolve this and unlock the value proposition in the project.”

Earlier in this article, we spoke about the global eruption of data centres which number about 5,697 commercially accessible and about 11, 800 counting private data centres. It should come as no surprise that 45% or about 3,391 of those are located in the United States with Virginia (537), Texas (304) and California (302) at the top of the list with the most facilities. Germany (529), the U.K. (523), China (449) and Canada (336) are next on the list. It’s expected that the Asia-Pacific region will eventually build out more than other world regions by the end of the decade. It’s important to point out that these numbers change rapidly with more data facilities coming online constantly.

A prime example is the Province of Alberta’s push to attract these tax-revenue producing entities. The province has 22 operating centres currently spread out between the two major centres of Calgary and Edmonton and other parts of the province with 29 more major centres in the que on the Alberta Electric System Operator’s Large Load Project list. Like other regions with aspirations of becoming data centre hubs, Alberta is trying to balance its existing power supply with the ever-increasing need for more power.

That power situation is not lost on those corporations who are developing these facilities and, as a result, alternative energy resources have been made priorities as evidenced by the Wonder Valley project above and other facility providers. A number of centres will be connected to the grid, drawing power from province’s natural-gas generated supply, but a significant number are planning to build their own on-site natural gas power generation plants, called “Behind-the-Fence”.

The emergence of a data centre colossus

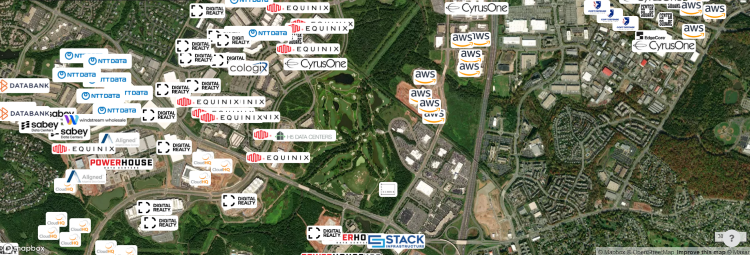

The abundant supply of natural gas is a major reason why this province is drawing significant attention. Compare that situation to what is happening in Northern Virginia, the northern half of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Known as Data Centre Alley, and located in Loudoun County, basically a suburb of Washington D.C., it’s considered the world’s largest and most concentrated region of data centres and is host to 70% of the world’s Internet traffic.

In a way, some parallels could be drawn between the situation which led to Loudin County sprinting to the top of the data center list and the objective which the Province of Alberta has set for itself through its AI Data Centre Strategy announced in December of 2024. In a January 2025 blog, service technology brokerage UPSTACK of New York provides a timeline of Data Center Alley and a fascinating look into the history of Internet development in North America.

The seeds for Northern Virginia’s data centre hub were planted in the early 1990s when several Internet network providers in Virginia created an Internet Exchange (also known as a Peering Exchange) by linking their systems together in a fibre network. Then, a name out of the past – America Online (AOL) - selected the area for its headquarters opening the door for the installation of more fibre and power infrastructure. Soon, a combination of reasonably priced land, low electricity costs and a skilled workforce attracted major companies like Verizon, Orbital Sciences, Telos and Equinix Inc, the world’s largest colocation data centre (a specialized data center which rents out space for other companies to install their own servers). And that fibre-optic/Internet infrastructure buildout continues with the recent commissioning of United Fiber & Data’s network from Virginia to New York City.

According to various sources including Loudin Economic Development (LEC), the primary attractors were: access to three low-latency, high-capacity intercontinental subsea cables connecting Virginia Beach with Europe and South America; cheap land; power rates 28% below the US national average; incentives such an exemption from the 6% sales and use tax for servers and server-related equipment; and significantly, the county’s Fast-Track Commercial Incentive Program “designed to streamline the development process, provide process certainty, reduce approval times and provide a central point of contact.”

An important note is that in the case of the Commonwealth of Virginia, although its state government has supported data centre growth by legislating certain regulations, it has also made it clear that data centre zoning decisions are made at the local government level and it’s those individuals and their decisions which have led to the region’s current technology status. One of those significant decisions came this past March when Loudoun County Board of Supervisors approved a Zoning Ordinance amendment “making data centers a special exception use in zoning districts in which they were previously a by-right use. By-right applications are approved administratively through the county’s site plan process, whereas special exceptions require a legislative process involving staff review and public hearings before the Planning Commission and the Board of Supervisors.”

Increasing the oversight of data centre approvals came after local residents complained about the facilities creating too much noise and being constructed in inappropriate areas such as beside residential neighborhoods.

Of the vastness of the U.S. Eastern Seaboard’s communications network labyrinth, there is no argument. Approving and building the infrastructure has probably been the most streamlined aspect of the Northern Virginia data centre ecosystem. As Loudoun Economic Development likes to point out, “There has not been a single day without data center construction in Loudoun in more than 14 years.”

But with all of the questions being tossed around about providing power to drive this ecosystem, how does Loudoun County do it? Let’s turn to the Virginia State Energy Profile supplied by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The profile states that in 2023, natural gas accounted for 55% of Virginia's total in-state electricity net generation, nuclear power supplied 32%, renewables—mostly solar energy and biomass—provided 12%, and coal fueled 2%. More than four-fifths of Virginia’s natural gas production came from coalbeds, and the state accounted for about one-tenth of the nation’s total coalbed methane production.

While that is the breakdown for Virginia’s current power sources, it doesn’t address the fact that unconstrained demand for power in Virginia is projected to double within the next 10 years, with the data centre industry being the main driver, according to an independent forecast commissioned by the state’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission. That demand is creating conflict with Virginia’s Clean Economy Act (VCEA) which requires the state’s two major utilities to provide 100% carbon-free electricity by 2045 (Dominion Energy) and 2050 (Appalachian Power). For instance, the power demand has forced some power generators to back off from shutting down coal plants which had been slated to close as early as this year.

Everyone wants in on the game

As Data Center Valley continues its eye-watering infrastructure expansion, but faces fundamental energy questions this brings us back to Northern Alberta and the provincial government’s charge to not only become competitive in attracting data centre hubs but to become “North America’s destination of choice for AI-enabled data centre investment” according to its AI Data Centre Strategy. That’s a tall order considering the various areas around the world competing for that same goal.

It’s no wonder that global regions are doing their best to attract the energy gobbling facilities. The benefits are tempting; as the State of Virginia’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission notes - the data centre industry is estimated to contribute 74,000 jobs, $5.5 billion in labor income, and $9.1 billion in GDP to Virginia’s economy annually. Most of these economic benefits, though, derive from the construction phase rather than data centres’ ongoing operations. Localities with data centres can collect substantial tax revenues from the industry, primarily from business personal property and real property (real estate) taxes.

And, as data centre developers emphasize, these benefits don’t end when construction is completed. “These are not short-term projects,” says Ken Hughes, Vice-Chair with Beacon AI Data Centers. “They will remain in operation for 15 to 20 to 30 years at a minimum.” Beacon announced in January of 2025, that it has six facilities in the Alberta Electric System Operator (AESO) que for Alberta sites with a total investment of about $10 billion will bring 1.8 GW capacity for hyperscalers with a total pipeline of 3.8 GW. Beacon calls its data centre infrastructure cutting-edge, according to the press release, in that it will utilize flexible, modular, and quickly deployable building techniques so hyperscalers can rapidly scale up infrastructure.

In addition to the economic benefits, Hughes feels these projects help to strengthen the workforce and support the educational institutions that the developers will work with to boost the workforce. And for the Province of Alberta, in particular, Hughes is adamant that the government’s strategy of attracting data centres and building upon its greatest assets, that of a world scale natural gas resource, will be transformational for the province.

While governments the world over scramble and pitch for the biggest and most data centre facilities, it’s important to take into account some unforeseen, or perhaps, disregarded negative aspects for those who live within the reality of these imposing facilities. That’s a topic for another conversation, but the following article from The Washington Post about residents living in the Data Centre Alley in Northern Virginia provides relevant comment about the benefits and disadvantages of this phenomenon.